Perhaps someone noticed the robot’s iridescent sheen, or the hexagonal head that abruptly rotated of its own volition. In fact, those were rather common qualities in robots on Starship PM15xB. Yet, no one noted the delicate foreign markings on this robot’s surface. No one noticed the gentle sway as the robot hovered above the floor, whereas other robots glided across the shiny aluminum on three nonskid, rubberized wheels.

Perhaps someone noticed the robot’s iridescent sheen, or the hexagonal head that abruptly rotated of its own volition. In fact, those were rather common qualities in robots on Starship PM15xB. Yet, no one noted the delicate foreign markings on this robot’s surface. No one noticed the gentle sway as the robot hovered above the floor, whereas other robots glided across the shiny aluminum on three nonskid, rubberized wheels.

A group of students strode down the landing dock with cacophonous voices, their garments emblazoned with the red and blue of their affiliated nation. A short boy with orange hair generously tossed the too-yellow peelings of a cloned Starfruit on the ground, inches away from the receptacle, as he tended to do for all Recyclebots.

It did not retrieve the boy’s trash. Instead, the robot’s green laser eyes flashed for a mere hundredth of a space-time second, and a holographic file of the undisposed waste soared across the universe.

This visitor hid in plain sight. The inhabitants of PM15xB depended on artificial intelligence for everyday living, and the robot was equipped with an advanced Incognito Mode. Discovery by a native being could result in a failed mission, but the most important feature of this alien robot was what it carried inside its hollow innards.

The boy and his companions passed through the Antiquities classroom gate, one-by-one. The mechanized gate scanned each and every student’s workstations, grading homework in an instant and simultaneously checking Memory Book assignments for completion. A pleasant ding-ding indicated that scanning was complete and that assignments were satisfactory.

Zeb never received the gratifying chime. He stepped into the scanner. An angry buzzing filled his ears, and he swiped a strand of fiery hair from his eyes. The class instructor glared at him, her gloved hands balled up on her pre-polymer-clad hips.

“Zebulon! Why won’t you complete your Memory Book?” Miss Aurora huffed. He looked back at her with big, round eyes and swore that, truly, he had no recollection of the Old World. Of course, he really did; he simply had no desire to relive the old, gravitationally orthodox ball of dirt.

On the Old World, up could only ever be up, and down, only down. To catch a fly ball, he positioned himself underneath it and consciously stuck a tentative hand into its speeding path. Here, in zero gravity, he just fired up his pressurized Manu-Unit and soared after it.

On the Old World, he cleaned his sleeping quarters, prepared his own meals, washed his own garments. Trash was sorted by hand – perishables, glass, aluminum, paper. On the Starship, Nanobots and Biobots completed those chores for him.

Zeb loved his life on the space station, and he intended to never leave.

The robot’s internal clock ticked. Finding suitable equipment storage was the first mission mandate.

Laser eyes switched on and scanned the area. No life forms detected.

The robot wavered along, heavy, across the dock and around a metal-walled corner into the school. A hallway loomed just ahead, bright and shiny, rows of pods lining its sidewalls.

Innumerable invisible beams scanned all the pods simultaneously. They locked on a single pod, and the robot floated down the hall, stopping in front of the pod marked 865. An invisible slot on the bot’s upper trunk materialized, and a multi-jointed arm shuttled outward. At the arm’s end, a jointed claw twisted the pod’s handle, and the door eased open. The contents amounted to a Manu-Unit headset and gloves, a ball made from synthetic fiber and a synthetic club.

The robot’s front panels clicked open, and an inner shelf presented a large grey box filling the body cavity. Mechanical rotators moved the box forward, setting it onto the floor. The robot reassembled itself, picked up the equipment box, now using two arms, and placed it inside the chosen pod. The door swung back and latched into its closed position.

Cyborg 1176, Intergalactic Cerberus, report follows: Stationing on Starship Planet Model 15xB: Completed. Mandate 1: Completed; one holofile logged. Mandate 2: Commencing.

A quick scan revealed that all had converged on the south side of the building. The robot zoomed down the hallway, thrusters humming with speed, toward the Antiquities class in session. It stopped just outside the entrance and peered inside.

The windowless lecture arena held 149 midyear students, plus one instructor. Diagrams, photographs and various other visual aids flashed across a large board at the helm. Insect, flower, leaf, musical instrument, coins. The students raised hands when they remembered an object and were called upon to share the memories with the class. The next image appeared to be quite primitive, black and grey, some form of sonography. The lighter parts of the image depicted a fetus, an unborn Being.

No hands.

Miss Aurora looked around the arena. “No one has any memories of babies?” Her gaze lingered to her left. “How about you, Zeb?”

Zeb didn’t respond. His head lay on his workstation, eyes closed. Seated directly behind him, Persephone landed a sharp kick to Zeb’s rear, and he jumped awake. The class stifled their laughter.

The instructor sighed, frowning. “I’ll ask again. Zeb, do you have a memory of babies?”

Zeb squinted. “Babies? No, why? Why would I remember babies?”

The robot’s eyes zoomed in on the orange-headed boy.

“Because your mother had the last biological baby in our history,” she replied, her face softening. “Surely, you remember something. Think hard, Zeb. This is important.”

“Why is this so important, huh?” Zeb hissed. “We’ve perfected genetics cloning. Human copulation was so… so animalistic… barbaric. Why do we need to remember the old ways of, well, anything?”

“We’ve had this discussion on several occasions,” the instructor said, shaking her head. “Our interest lies in the tools we once used, the implications of primitive processes and the bearing of them on our future. We want to explore the What, the Why, and the How. We cannot shape our future if we do not understand our past, Zeb.”

Zeb sighed loudly. “Despite all of that, I still don’t remember anything about babies. Why don’t you ask my mother?”

The silence was as vast as space itself.

“Zeb, I didn’t – “

“Please, carry on,” he huffed.

The robot recorded the exchange between Zeb and the instructor and sent the file to its superiors, noting the boy’s relationship to the holofile sent earlier. Once the transmission was complete, Cyborg 1176 detected movement. Class had dismissed, and the Beings would exit the lecture arena into the hallway in three… the robot floated to a corner away from the door… two… activated Incognito Mode… one.

Persephone trailed her friend through the mire to his pod. She jumped in front of him and leaned against the pod door. “Hey, do you want to talk about what just happened?” Her designer burnished hair eclipsed her golden face, one eye peering at Zeb, soft and warm, like melted chocolate.

“Why? What just happened?” he feigned.

She frowned. Her perfectly constructed button nose wrinkled, but not so much as to appear ugly. “Cut the crap.” She looked away and sighed. “I have to work on my Astronomy project tonight, but we’ll talk tomorrow, okay?” She cocked an eyebrow that would never need grooming.

Zeb squinted, and his bushy brows scrunched together, revealing where a wrinkle would form with age. His father bore an identical mark. “Yes, ma’am,” he mocked. Persephone nudged him the ribs and walked away. Zeb stared after her, a strange uneasiness in his belly.

He opened his pod, picked up his Manu-Unit headset, and stopped. A grey box sat in the bottom. Zeb glanced behind him, right and left, and slid the box’s lid to the side. Something flat, electronic, was inside, metal, with glass tubes and small lights. He recovered the box, put on his Manu-Unit gloves, grabbed the box, and kicked the pod door.

The robot observed Zeb carry the equipment down the hallway, pushing through the crowd. Cyborg 1176 was unable to move, playing the part of trashcan.

Pieces and parts of the alien equipment littered Zeb’s dormitory room floor. He’d tried to power the machine to deduce its function. When he realized he could not turn it on, Zeb deconstructed it.

“Whoa,” he breathed. He held up one of the thousand or so miniature syringes he’d found in an inner compartment. The needle’s point glinted under the overhead halogen light.

The syringe compartment attached to several glass tubes, possibly feeding through some type of scanner or detector, maybe even processing the substance by fractionation, then the resulting components stored in glass vials. The lights on top of the machine were labeled, but the words were indecipherable.

Zeb neglected his homework that evening, and he ignored an invitation via Satellpad from his dorm mates to toss around a ball. Not even the intermittent green flash just outside his door caught his attention.

Zeb rubbed the sleep from his eyes. His dream replayed in his mind, of a slender woman with red hair and freckled skin being stabbed by the machine with a thousand needles. He glanced at the floor, expecting to see the machine jumbled and strewn as he’d left it the night before. But it wasn’t there.

He tossed the covers back, jumped from his bed and padded barefoot to the grey box sitting in the corner. He lifted the lid. Empty. He spun around, dove onto the floor and peeked under the bed. Nothing. He stood, his fingers running through his ruffled mane.

His Memory Book lay open on the desk. Zeb shuffled a bit closer, his head cocked. The page before him had been filled with a drawing of such detail, such delicate intricacy, that it might have been taken for a digital image. It depicted a dimpled baby, his eyes shining bright and cheeks flushed with glee, swathed in fleece. Zeb glowered and flung the book shut.

On the landing dock, he rushed to Persephone, his face locked in a scowl. “Did you come into my room last night?”

She smirked. “Happy landings to you, too.”

“Did you?” he demanded.

“No,” she said. “Why would I be in your room?”

“You didn’t do this?” he said, holding out his Memory Book.

She sighed. “I don’t know what you’re talking about, Zeb.”

“Look,” he said, and he flipped open the book to the drawing.

Persephone gaped, taking the book in her hands. “Oh, Zeb,” she breathed. “This is… it’s so beautiful. In essence, you’ve exemplified two memories, the baby and… art. Antediluvian, yet mesmerizing.” She handed the book back. “You should be proud of yourself.”

“I didn’t do this!” he shrieked. “Someone else… if not you…”

Persephone’s eyes widened. “No, Zeb, I swear. I couldn’t have made this if I’d wanted to.” His freckled nostrils flared. “Hey,” she said, “don’t be upset… someone just left you a gift. You’ll finally be favored by Miss Aurora.”

The pleasant chime sounded as Zeb stepped through the Antiquities entrance, and Miss Aurora cried, “Zebulon, how wonderful! Thank the Moons!” He smirked as he sat in his seat. She did not call on him for the duration of the class, but whenever her gaze passed in his direction, her eyes shone a bit brighter.

After class, Persephone joined Zeb in his dorm room. She thumbed through his Memory Book. “Who do you suspect?”

“You.”

“I’ve already told you,” she laughed.

“There’s something else,” Zeb grumbled. He told Persephone about the machine. She examined the grey box that had once held it.

“Do you think whoever created the drawing also took the machine?” she asked.

“I can only assume so.”

“Then let’s assume this person will return for the machine’s box, or perhaps to leave you another gift,” she said, her voice quiet. “Let’s set up a trap.” They rummaged through Zeb’s storage crate and dug out some old Laser Tag gear. Persephone recalibrated the receiver vests to alarm when the lasers missed them, and Zeb tied string around the pistols’ triggers to make the lasers fire repeatedly. They tested pistol and vest positions until they were satisfied that the rig would catch any intruder.

Nanobots delivered their evening meals to Zeb’s room, and they cheered when the alarm went off. Persephone hugged Zeb, an excited goodbye, and Zeb waited alone in the dark, staring at the spine of his Memory Book on the desk until his eyelids grew too heavy.

WEEEOOOWEEEOOOWEEEOOOWEEEOOO!

Zeb scrambled to his feet, yelling “LIGHTS ON! LIGHTS ON!” The overhead lights blinked on, and he shielded his eyes until they adjusted. He stood on top of his mattress, his head twisting and turning to catch a glimpse of the artist-thief. The laser vest alarmed on without ceasing, but there was no one to be seen. A trashcan sat in the center of the room, blocking the pistol’s laser from reaching its target. Zeb glanced at his closed door, then ran over and flung it open. The hallway was empty, so he closed it back, and he disconnected the vests’ power source.

He sat on the floor. The robot wavered lightly, and Zeb leaned in. “Your markings…” he whispered. “They’re like the ones on the machine.” His hand ran over the surface, his fingers tracing invisible lines. “You’re not a Biobot, are you?”

The robot responded with a green flash. Zeb jumped back, and the robot zoomed underneath the desk, knocking the Memory Book to the floor. Another green flash.

“Stop it!” Zeb shouted. “Will you come out of there?”

Green flash.

“I don’t know what you think you’re doing-“

Flash. Flash, flash.

“-but I just want to talk to you!” Zeb growled, protecting his eyes.

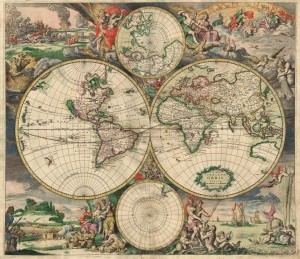

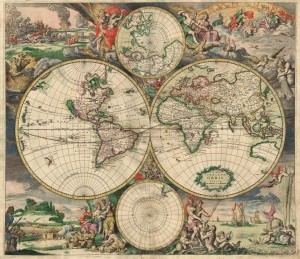

The robot’s appendages materialized, reaching out and snatching the Memory Book. All four phalanges on each of the robot’s hands morphed into needlepoints, and an inky substance flowed from their ends. Zeb’s jaw went slack, watching the image unfold. After only moments, the robot pushed the book away, its green eyes glowing steadily. The drawn image covered two pages, like a centerfold; it was a rendering of the Galaxy, complete with Zeb’s starship and the neighboring ships – all the PM15x models.

“How did you do this?” he asked after a long while of silence. The robot stared, motionless.

“Can you speak? Do you know my language?”

The robot took the Memory book and flipped the page. He wrote in perfect, straight lettering: “I am unable to communicate vocally. I understand all known languages.”

“Where are you from?” Zeb said.

“From a planet many light years away.”

“Tell me about it.”

“The home planet’s atmosphere is 78 percent Nitrogen, 21 percent Oxygen, and .9 percent Argon, with trace amounts of carbon dioxide and water vapor. The temperature on the surface ranges from –127 degrees F to 136 degrees F; the average temperature is 59 degrees F.

“The planet completes its elliptical orbit around the sun in an average solar year, 365.24219 days. The axis is tilted 23.45 degrees away from the perpendicular to its orbital plane, producing seasonal climate variations.

“The tilt of the axis causes different parts of the planet to vary in the way they are oriented towards the sun at different times of the year….”

Zeb interrupted the robot’s scribbling. “Okay, okay… that’s enough. Why are you here?”

“The mission objective is to collect organic data samples from the PM15x starships and send them to base, in addition to observing the inhabitants of PM15x starships.”

“You’re observing us and collecting samples? Why? What are you looking for?”

“My superiors want to know if your kind is worth saving.”

Zeb frowned. “What does that mean?”

“My counterparts have deemed your kind unworthy. You destroyed your home planet with pollution and overpopulation. The waters ran black with chemicals, the fields turned to poison and the native habitats died. My superiors deemed your kind a threat to the delicate balance of the universe.”

“We’re doing fine out here on our starships. We’ve developed new ways of living. We’re not hurting anyone,” he laughed.

“If I do not find sufficient evidence that your kind is beneficial to the universe, you will be destroyed.”

Zeb laughed harder. “Robot, I like you. You’ve got a good sense of humor, and that’s a difficult quality to find around here.” He stood up. “I’m Zeb. I’m the last natural-born of my kind, and I hate it. I don’t look like anyone else. I don’t have the perfect features or superfast reflexes… so I’m happy to be here in space. Space is kind of the great equalizer, you know? No one is faster or stronger than anyone else.”

The robot moved out from under the desk. It wrote: “This is why your kind is unworthy. You have abandoned nature.”

“No, robot, we abandoned it because it failed us. Nature gave us too many kids like me.” Zeb frowned. “Hey, do you have a name?”

“I am Intergalactic Cerberus, Cyborg 1176.”

Zeb smirked. “That’s a mouthful. Intergalactic Cerberus. I-C… I-N-C. Inc. Ink. How about that? Ink?”

“O-K.”

“Ink, did you take the machine I’d disassembled?”

“Yes. It is highly sensitive equipment. You should not have taken it.”

Zeb commanded the lights off and lay down. “I’ll find you a reason to like my kind. You’ll see.”

He slept and had another uneasy dream. The slender red-haired woman and Zeb were surrounded by faceless, ambiguous beings.

When Zeb awoke, Ink was gone. The Memory Book lay open on the floor. The page read, “Do not alert authorities to Ink’s presence. Ink will help Zeb find evidence worthy of saving.” Zeb sighed.

The happy chime followed Zeb into his Antiquities class. Miss Aurora beamed. She started the class as usual: “Are there any questions?” Today, Zeb raised a hand.

“Zeb,” she said, unable to hide her surprise, “yes? You have a question regarding Antiquities?”

He lowered his hand. “Did we abandon nature?”

“I’m not sure I understand what you are asking.”

“On the old planet, did our people abandon nature? Change and kill it when it we could’ve learned from it?” Zeb’s voice was strong.

“Well, I don’t believe ‘abandon’ is the correct word,” the teacher said. “I do believe we made improvements, made some processes easier on ourselves… such as DNA manipulation. We’ve all benefitted from that development.”

“But how did we know what the result would be? How did we know there wouldn’t be major consequences to manipulating DNA?”

“Because of scientific research and testing. A great amount of time and resources went into the study of DNA manipulation, and all other scientific improvements, I’ll add, so that we know we are benefitting our kind, not hindering.”

The other students began to chatter. Zeb hardly spoke in class, nor paid attention, and his sudden interrogation was cause for concern. A boy’s voice in the back of the arena called out, “He’s just jealous because he’s natural-born.”

“No, that’s not what I’m talking about, but that brings up an interesting point,” Zeb called out above everyone. “What is so wrong with being natural-born? Why does everyone have to be the same? Like robots?”

As Miss Aurora struggled to regain control of the class, Ink listened just outside the door and recorded. The sound file traveled across the light years along with a report:

Mandate 2: Completed; multiple samples and holofiles logged. Awaiting instructions for Mandate 3.

Persephone stalked Zeb all day. He ducked into the restroom during lunch and hid behind a Biobot in between classes. So, she waited outside his dorm room, twisting a strand of hair through her fingers. Before he could reach the end of the hall, she besieged.

“What happened last night? Did the trap work? Who was it? And what caused the confrontation in Antiquities?”

He stopped her from entering his room. “Nothing happened. No one came in.”

Her face scrunched beautifully. “But… your Memory Book. I heard the chime.”

“Oh… right,” he breathed. “I… I did it myself… this time. I thought it would be nice… for Miss Aurora. She was so happy yesterday….”

“And then you blasted her,” Persephone snickered.

Zeb faked a yawn. “I’m really tired… didn’t sleep well. I’ll talk to you tomorrow.” He shut the door and rushed to pull out his Memory Book. Then he sat on his bed and flipped through it, reading over Ink’s responses, silent and thoughtful.

Ink nudged Zeb awake with the Memory Book. Zeb commanded the lights, took the book and looked at the page the robot presented. A woman with a full, happy face, her eyes and her lips stretched in smiles. Her copper hair was drawn up into a loose bun high on her head, and she wore thick-rimmed glasses low on her nose. Her white shirt was pulled tight across a belly heavy with child.

“Who is this?” he whispered. He swallowed hard, his face stern.

Ink reached across the bed and wrote one word: Mother. A tear slid across Zeb’s cheek and followed the curve of his nose. The robot reached across again and wrote, “You have her eyes.”

Zeb smiled, and whispered, “I do, don’t I?” He pushed the book away, and swiped at his nose. “How’d you know?”

“A holograph of this image is available on an obsolete network hard drive. It seemed that you should know that you are worth saving.”

“Thank you, Ink.”

“You are welcome.” And then, “Friend.”

The two sat still and wordless, the alien robot and the last natural-born boy.